Barely a Book Club #12: One for the Lord, One for the Serf

Last call at the Red Ox Inn.

This is the last installment of our series on Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts. You can read the previous entries here and here.

One night early in his walk across Europe, Patrick Leigh Fermor stepped out of the darkness and into the old university city of Heidelberg. Drawn to the glowing windows of an establishment on the main street, he found himself in Zum Roten Ochsen, the Red Ox Inn, a student haunt founded nearly a century prior in 1839 by the Spengel family, who still operated the place. “I clumped into an entrancing haven of oak beams and carving and alcoves and changing floor levels,” he writes. “A jungle of impedimenta encrusted the interior—mugs and bottles and glasses and antlers—the innocent accumulation of years, not stage props of forced conviviality—and the whole place glowed with a universal patina. It was more like a room in a castle, and except for a cat asleep in front of the stove, quite empty.”

“This is the moment I longed for every day,” he writes of his welcome, sitting at a table, writing, drinking wine, nibbling on cheese and bread, chatting in broken German with the innkeepers. He befriends their son, Fritz, who shows him around town over the next couple of days, and in a memorable encounter, kicks out a local Nazi when he insults Fermor at the pub on New Year’s Eve.

The next day it is 1934. Fermor moves on, leaving Heidelberg and the Spenglers behind. It’s impossible not to wonder what happened next to the family, to Fritz. Fermor certainly did, as he writes, “My sojourn at the Red Ox, afterwards, was one of several high points of recollection that failed to succumb to the obliterating moods of war.” During the writing of A Time of Gifts, more than 40 years later, he decided to find out, and he wrote a letter, addressed to “the proprietor,” to the Red Ox, Heidelberg. The reply came from Fritz’s own son, who reassured him that the inn was still in business, but that Fritz had died at the front six years after their meeting, in Norway where Fermor’s own regiment had been fighting at the time.

On reading this, of course I had to do the contemporary equivalent of writing a vaguely-addressed letter to Heidelberg, so I looked up the Red Ox Inn and found that, to my delight, it still exists, still looks exactly how I imagined it, and is still run by the Spengler family.

All travel writing inevitably, instantly becomes time writing. You read not just about places, but the vanished, partially or otherwise, worlds they inhabited. Reading A Time of Gifts, what I loved the most were the moments and characters that would otherwise be irretrievable, that exist for us now only because Fermor saw and heard them.

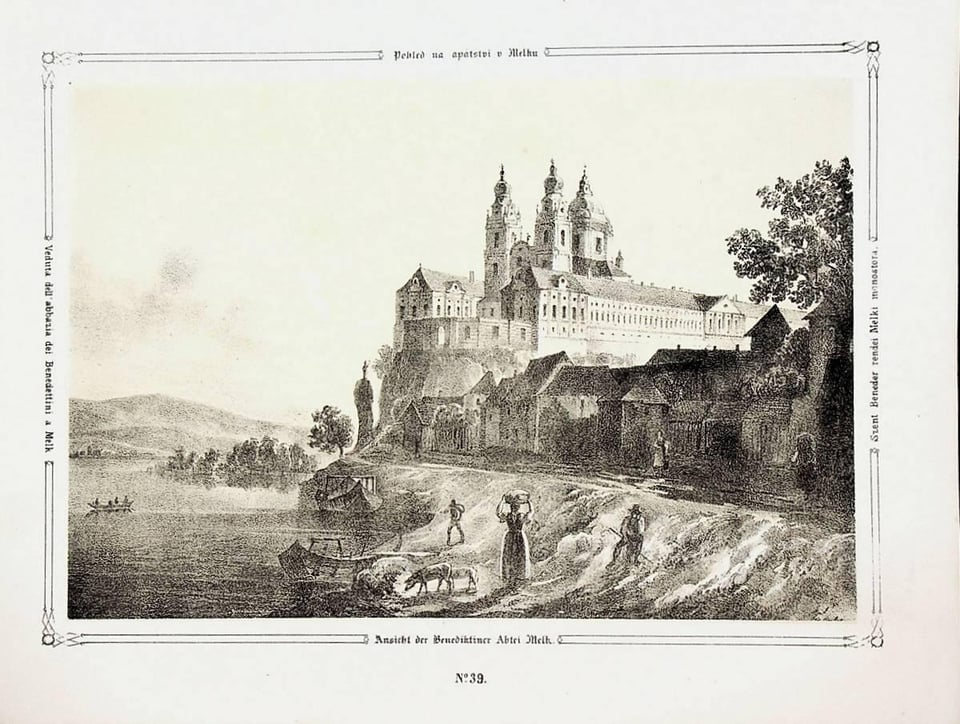

I will admit that Fermor’s digressions about art and architecture were, at times, slow going for me, although I appreciated the youthful enthusiasm and epiphanies he was able to reproduce so many years later. And some of the writing is genuinely vivid, like his musical description of the baroque Melk Abbey:

Overtures and preludes followed each other as courtyard opened on courtyard. Ascending staircases unfolded as vaingloriously as pavanes. Cloisters developed with the complexity of double, triple and quadruple fugues. The suites of state apartments concatenated with the variety, the mood and the the décor of symphonic movements. Among the receding infinity of gold bindings in the library, the polished reflections, the galleries and the terrestrial and celestial globes gleaming in the radiance of their flared embrasures, music, again, seemed to intervene. A magnificent and measured polyphony crept in one’s ears.

Pure synesthesia. I can hear the palace as clearly as I can see it, even though I don’t have any idea what a “pavane” is, nor could I distinguish between a triple and quadruple fugue.

But it’s when Fermor actually encounters other human beings, spends time with them, gets into scrapes and misadventures, goes to parties where he’s not invited, that the book truly sings. He captures the fast, intense friendships of travel, in which we reveal ourselves to people completely with all the freedom of knowing we will never see them again.

Fermor enters Vienna on an ox cart with a farm girl named Trudi, only to find there’s an attempted coup in progress. “I took the egg basket, and Trudi the drake, and she put her free arm companionably through mine. The drake, which had been asleep most of the journey, was wide awake now and quacking frequently.”

He meets an enterprising, mustachioed Frisian named Konrad in a hostel and they spend a week ringing the doorbells of bourgeois apartments. Fermor invariably charms the inhabitants into paying him to sketch their portraits. These people are largely nameless and their fates in the dark years to come unknown—do they have descendants who remember them today?—but they live on in his descriptions. “His rosy face was adorned with one of those waxed and curled moustaches that are kept in position overnight by a gauze bandage.” “A pretty ash-blonde girl tiptoed out of a pink bathroom on pink mules trimmed with swan’s down, tying the sash of a turquoise dressing-gown.” “Shed evening clothes scattered the floor of the next flat—tails, a white tie, an opera hat, gold high-heeled shoes kicked off, a black skirt twinkling with sequins, spirals of streamers and a hail-drift of those multicoloured little papier-maché balls that are sometimes flung at parties. The face of the tousled and pyjama-clad young man who had crept to the door displayed familiar symptoms of hangover.”

As Fermor reaches Vienna and continues past its former battlements (torn down by Franz Josef I to Johann Strauss’ “Demolition Polka”) and onwards to the once and future Slovakia and on a detour to Prague, my attention intensified. Reading, I felt a strange slackening of one kind of tension and tightening of another. We were no longer in the steaming, fetid cauldron of National Socialism, where portraits of Hitler hung on on tavern walls and every other stranger he encountered may have been a fervent Nazi, but we were getting closer to the homes of many, many of their eventual victims.

Bratislava was full of secrets. It was the outpost of a whole congeries of towns where far-wanderers had come to a halt, and the Jews, the most ancient and famous of them, were numerous enough to give a pronounced character to the town. In Vienna, I had caught fleeting glimpses of the inhabitants of the Leopoldstadt quarter, but always from a distance. Here, very early on, I singled out one of the many Jewish coffee houses. Feeling I was in the heart of things, I would sit rapt there for hours. It was as big as a station and enclosed like an aquarium with glass walls. Moisture dripped across the panes and logs roared up a stove-chimney of black tin pipes that zigzagged with accordeon-pleated angles through the smoky air overhead. Conversing and arguing and contracting business round an archipelago of tables, the dark-clad customers thronged the place to bursting point. (Those marble squares did duty as improvised offices in thousands of cafés all through Central Europe and the Balkans and the Levant.)

The Jewish population of Slovakia around the time of Fermor’s visit would have been around 136,000; today it is estimated at about 2,600.

Pictured above is another 19-year-old, hostel-haunting traveler to Prague, a much less erudite and heroic one: me. Like Fermor, I found it a “bewildering and captivating” town. I also found myself stuck there for much longer than I had planned, unwilling to shift with the current, fixed there by teenage romanticism, cheap beer, and the promise of adventure around the corner.

I chuckled to myself when I read that Fermor was drawn into conversations about whether the castle that dominates the skyline was the same one as in Kafka’s novel. I must have had the exact same conversation, only the subject, and that observation in particular, would have been a lot fresher for him. For me it was literary history; for Fermor, the book would have been published only eight years prior, and would have been contemporary as Zadie Smith or George Saunders is to us now.

In the spirit of Fermor posting a note to the Red Ox in the late 1970s, I sent an email to the address I found on their website inquiring after the family and asking whether they still had his original letter.

Hours later, I received a reply from Philipp Spengel.

Dear Mark,

Thank you for your email and nice words about my family, who still run the Red Ox Inn, the 6th generation to do so over the last 185 years.

My wife and I took over the business in 1995, and we have three nice daughters (27, 25 and 18), who probably won’t take over… but we’ll see what they do.

In any case, a lot of people have come around after reading the book.

I don’t have the original letter from the 1970s, as my father passed away in 1984.

If you’d like to come to our old student pub, I’ll show you a lot.

Kind regards from Heidelberg,

Philipp

Well this was it: our fourth Barely a Book Club.

Did you like it? Did you make it through? Are you still reading? Let me know below.

I haven’t 100% made up my mind, but I think our next selection will be Full Tilt: From Ireland to India With a Bicycle, by Dervla Murphy, an account of a solo trip made in 1963 by the author. We haven’t had nearly enough bicycling content here, so this feels right. Read it already? Tell me what you think.

Until then, you can always find me at Something Good, or right here.

-

Mark,

Thank you for this series of posts on PLF's 'A Time of Gifts'. I didn't read along as I've read it a couple of times before, and it's one of my favourite books. Or perhaps not favourite, but admired, or influential? And well done for emailing the The Red Ox Inn!

Definitely go for 'Full Tilt' next! One of my most treasured books is an extremely battered first edition of this that was given to friends of my parents in Nepal in 1965.

Best wishes, Huw

Add a comment: