Barely a Book Club #14: A Dervla Delirium

“If anyone ever asks you to drive three donkeys and a foal for twenty-four miles through the Karakoram Mountains, be very firm and refuse to do so."

This is the second and final entry in our series on Dervla Murphy’s Full Tilt: Ireland to India on a Bicycle. Roxane Hudon’s inaugural post can be found here. As always, you don’t need to have read the book first.

“If anyone ever asks you to drive three donkeys and a foal for twenty-four miles through the Karakoram Mountains, be very firm and refuse to do so—it really is more than flesh and blood was ever meant to endure.”

So begins Dervla Murphy’s entry for the 9th of June, 1963, written in the valley of Gupis in what is today the administrative territory of Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Gilgit-Baltistan is home to some of the highest mountains on the planet (K-2 and Nanga Parbat being two of the best known), treacherous, terrifying roads (The Canadian government: “Do not travel by road to Gilgit-Baltistan province”), and 60 years ago Dervla Murphy crossed it on a rickety one-speed bicycle, and on one occasion, driving three donkeys and a foal. The three-donkeys-and-a-foal story is only a single, off-handedly described incident in a book full of stories that most people would dine out on for the rest of their lives.

The first pages of Full Tilt couldn’t help but remind me of the opening of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; Murphy departed from Dunkirk, not the Hook of Holland, but otherwise in January, around the same time of year, and similarly alone.1

I shall never forget that dark ice-bound morning when I began to cycle east from Dunkirk; to have the fulfilment of a twenty-one-year-old ambition apparently within one’s grasp can be quite disconcerting. This was a moment I had thought about so often that when I actually found myself living through it I felt as though some favourite scene from a novel had come, incredibly, to life.

But while Fermor’s journey, by foot, had Istanbul as its goal, Murphy basically zooms through Europe in the book’s introduction; the first chapter proper opens with her arriving in Tehran.

(It’s in that introduction that she tells the incredible, often-repeated story of defending herself from a pack of wild wolves outside Zagreb with a pistol. Another writer might have written an entire book about this, or at least spared it a whole chapter.)

It took me a little while to get used to one of Murphy’s stylistic peculiarities; she constantly refers to herself in the first person plural, and I had to keep reminding myself that when she writes “we,” she’s talking about herself and Roz, her bicycle. It’s a bit tired to say that Roz is a “character” in the book, but she’s certainly a presence, and she suffers just as much as Murphy in their unbelievable treks through deserts and up and down mountain ranges.

What Murphy goes through over the course of her travels is truly amazing; she must have been made of iron. Some of the sequences are so harrowing, so delirious, I can barely believe she survived them. Biking through the mountains of Chilas on a day when the temperatures reached 114° F, she writes:

I had to walk all the way as the first twenty miles were through very deep sand, up and down very steep hills, and after that I was too dizzy from the heat to balance on Roz, even when the track was level. By 7 a.m. the sun was so hot that I was saturated through with sweat and as we only came to one nullah for wetting, cooling and refilling the water bottle, dehydration became my fear. I found shade once, under a rock, and slept very soundly from 1.40 to 2.50 p.m., although lying on sharp flints.

These privations, though graphically described, don’t ever seem to deter her in the slightest, nor does she ever seem boastful. They’re just astonishing details in a book full of them; I practically gasped, for instance, when she described seeing the Buddhas of Bamiyan, the enormous sculptures that had stood since the 6th Century in a valley in Afghanistan until Taliban forces destroyed them some 40 years after her visit in 2001.

What really struck me, reading Full Tilt, was despite the wild landscapes and unbelievable physical challenges, not to mention the dangers of being a solo woman tourist on a bicycle in the 1960s, it’s the people that Murphy comes across that fascinate her the most.

She is equally comfortable sleeping in the huts of impoverished family and the palaces of Rajas, although you get the sense she actually prefers the former. Wealth, status and the amenities of civilization don’t impress her, and it’s clear she’s eager to make a genuine connection with the people she meets.

From an appreciation written by after her death by Hugh Thomson:

On that first journey through Afghanistan on her bike, Dervla was appalled to meet foreigners who never talked to an Afghan, let alone entered their homes: “All they had done was photograph them.”

The instinctive sympathy she displays is a foretelling of the work she would go on to do over a very long career, writing about places as besieged and beleaguered as Northern Ireland in the 1970s, Gaza in 2011, and many, many more, telling stories that many didn’t want to hear.

At the same time, some elements of Full Tilt have not aged well. Murphy’s reflexive disdain for modernism often leads to a romanticization of poverty—she sniffs at the idea of universal literacy and makes a lot of dubious claims about “old-fashioned” ways of living and the role of women. These ideas conflict rather violently with her descriptions of malnourished children and under-resourced hospitals.

There are also, it has to be said, not a few moments of outright racism; passages which are hard to square with the writer who so unflinchingly stood with the oppressed in the decades to come, and which I have to attribute to youthful ignorance and “the times” in which the book was written. It’s my right to forgive or excuse her, but on the whole I think her record shows her to have been plainly a force for good and truth in the world.

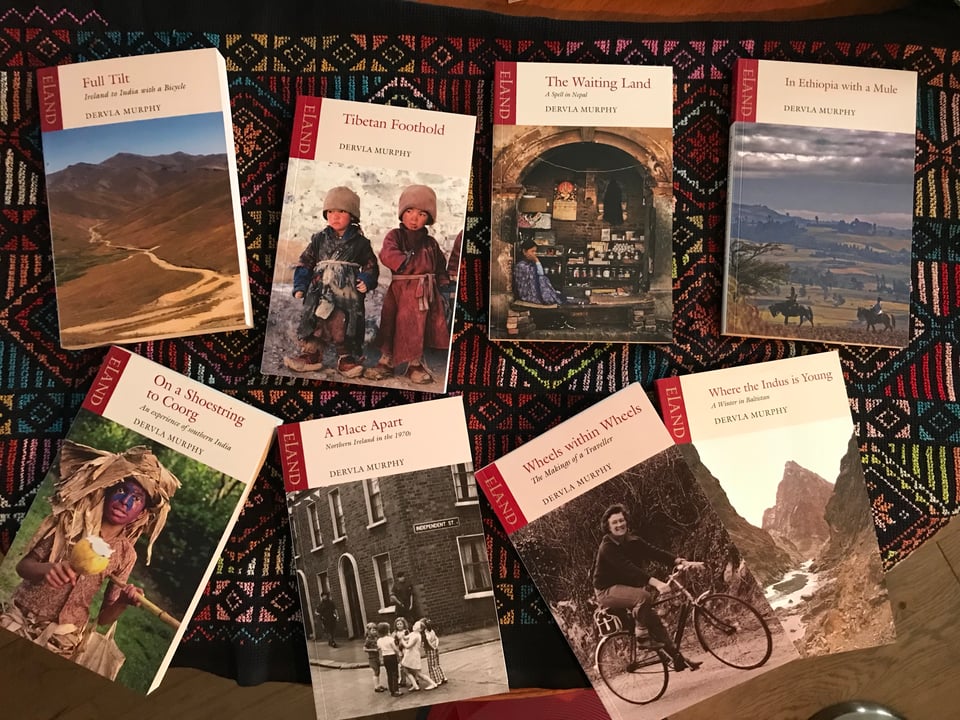

Throughout the book, Murphy describes herself either taking photographs or searching fruitlessly for (as she charmingly puts it) “a film” for her camera in local bazaars. It made me wonder: where are the pictures she was taking along this journey? I needed to see them! I wasn’t even discouraged by a passing comment in the book’s final pages that “all the photos [I’ve] taken so far are worthless.” So I emailed Eland Books, publisher of the edition of Full Tilt I was reading, and many of her other titles.

Literally minutes later, I received a reply from Barnaby Rogerson, Eland’s publisher. “She was a hopeless photographer, but good in all other ways,” he wrote, putting rest to my dream of seeing those original shots.

He was good enough, though, to send along a photo of the writer herself, taken just before a talk she was about to give at the Royal Geographical Society in 2019. It’s there, enjoying a pint, that we’ll leave her.

That ends our series on Dervla Murphy—a truly astonishing writer I feel privileged to know better now, and whose works I plan on returning to. I’m still mulling over our next selection, although I’m leaning towards a two-book combo by a single author, one fiction, one non. Can you guess who?

Please let me know what you think of Dervla and her journeys below in the comments, and don’t forget to subscribe and/or tell a friend if you like what you’ve read here.

A Time of Gifts is set 30 years earlier, in 1933, but was written a dozen years after Full Tilt, so who can say which direction inspiration might have flowed. ↩

Add a comment: